Use the promo code GO26 at checkout

Cornwall is not quite like the rest of England. It never has been. Separated from the rest of Britain by the River Tamar and 300 miles of peninsula that narrows to a point at Land's End, it developed its own culture, its own language, its own character, and its own fierce sense of identity long before anyone thought to call it part of a United Kingdom. The Cornish are a Celtic people — closer in ancestry and tradition to the Welsh, the Scots, and the Bretons of northwest France than to the English who border them to the east. Their ancient language, Cornish, died as a first language in the 18th century and has been in active revival ever since. Their flag — the black and white cross of St Piran — flies everywhere, often alongside, and occasionally instead of, the Union Jack.

All of which is to say: Cornwall rewards the traveller who pays attention. There is more here than beaches and cream teas, though both are extraordinary. There is history, myth, landscape, art, food, and a coastline so dramatic that it has been inspiring painters, writers, and poets for two hundred years without showing any sign of running out of material.

The land at the edge of the world

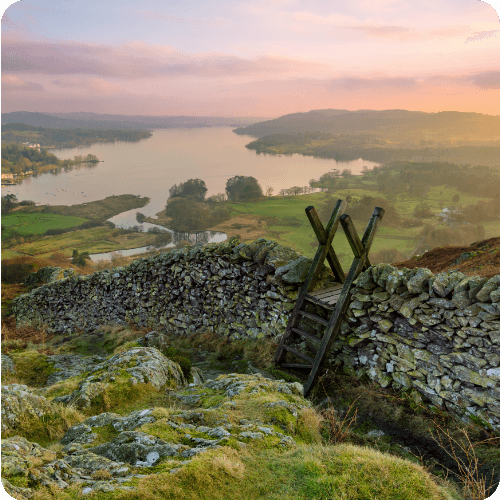

Cornwall occupies the far southwest of England, jutting 70 miles into the Atlantic like a geographical declaration of independence. It has 300 miles of coastline — more than some countries — and almost no point in the county is more than 16 miles from the sea. The light here is different from anywhere else in Britain: clearer, sharper, brighter, a quality that has attracted artists since the 19th century and continues to draw them today. The Newlyn School of painters, who worked in and around the fishing village of Newlyn near Penzance in the 1880s, produced some of the finest realist painting in British art history. Their successors — the St Ives modernists, including Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson — transformed that same quality of light into abstract sculpture and painting of international significance. The Tate St Ives, opened in 1993 in a former gasworks overlooking the harbour, is one of the great small art galleries in Britain.

The landscape is ancient in ways that reveal themselves slowly. Cornwall has more prehistoric monuments per square mile than almost anywhere in Britain — standing stones, stone circles, fogous (underground stone chambers whose purpose remains debated), and cliff-top burial chambers that predate Stonehenge. The Merry Maidens stone circle near St Buryan, perfectly preserved in a field just off the road, dates to around 2500 BC. The Cheesewring on Bodmin Moor — a natural stack of granite slabs balanced with implausible precision — has been a site of human significance since the Bronze Age. Bodmin Moor itself, rising to 420 metres at Brown Willy (the highest point in Cornwall), is one of the last true wildernesses in southern England: a landscape of granite tors, ancient field systems, and moorland bog that has resisted development, agriculture, and the 21st century with impressive determination.

A history written in tin and copper

Cornwall's history is largely the history of mining, and it is a history of staggering scale. For two thousand years — from Roman times to the early 20th century — Cornwall was the most significant source of tin and copper in the known world. Phoenician traders came here for tin before the Romans arrived. Roman Cornwall supplied the empire. By the 18th and 19th centuries, Cornish mines were producing two-thirds of the world's copper supply, and Cornish miners were the most sought-after skilled workers on the planet.

The engine houses — those distinctive stone towers with their attached boiler houses that punctuate the Cornish coastline and moorland — are the physical legacy of this industry. There are hundreds of them, many now roofless and ivy-covered, perched on clifftops above the sea or rising from the middle of heathland, and they are among the most evocative industrial ruins anywhere in Britain. The Cornish Mining World Heritage Site, designated in 2006, covers ten separate areas of the county and tells a story of human ingenuity, brutal labour, and eventual decline that shaped not just Cornwall but the entire industrialised world.

When Cornish mines collapsed in the face of cheaper copper from South America and tin from Australia in the late 19th century, the resulting diaspora sent tens of thousands of Cornish miners — the best in the world at what they did — to South Africa, Australia, the Americas, and beyond. The phrase "Cousin Jack" — the Cornish nickname that travelled with them — is still used by communities of Cornish descent from Michigan to Johannesburg. Wherever you find a hard rock mine from the 19th century, you tend to find Cornish surnames not far behind. The Cornish built the mining industry of the modern world, then watched it pass them by.

The food

Cornwall takes its food seriously in the way that places with access to extraordinary raw ingredients tend to. The fish — landed daily at ports from Newlyn to Looe — is some of the finest in Britain: Cornish mackerel, crab, lobster, sole, and sea bass prepared in kitchens that understand they don't need to do very much to something this fresh to make it extraordinary.

The Cornish pasty needs no introduction — its history, its Protected Designation of Origin status, its mining origins, and the eternal debate about whether the crimping goes on the side or the top are all covered in our food article. Suffice to say that eating a genuine Cornish pasty, made in Cornwall, from a bakery that has been making them for generations, is a different experience from eating one anywhere else. The comparison to what you buy at a railway station is not worth making.

And then the cream tea. Clotted cream — thick, golden, slightly crusted on top — is a Cornish invention, made from the rich milk of Cornish dairy herds by a process of slow heating that concentrates the fat into something so dense and extraordinary it barely qualifies as the same food group as the cream you put in coffee. The question of whether jam or cream goes first is, in Cornwall, not a question at all. Jam first, cream on top. The Devonians disagree. This has been going on for some time and shows no sign of resolution.

The places: a few places you must see

St Ives - A harbour ringed by three beaches, whitewashed and granite cottages climbing the hillside, lanes too narrow for comfortable progress, and a quality of light that has been drawing artists since the 19th century without showing any signs of exhaustion. The Newlyn School painters came first in the 1880s. The St Ives modernists — Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, Naum Gabo — arrived in the 1930s, fleeing Europe and finding in Cornwall's far western light exactly the conditions they needed. The Tate St Ives, perched above Porthmeor Beach, continues the tradition. The Barbara Hepworth Sculpture Garden, in the studio where she worked until her death in 1975, is something else — her large bronze and stone sculptures standing in the subtropical garden she planted, her tools still on the workbench inside, glimpses of the sea visible above the garden walls. It is one of the most moving artist's spaces in Britain, and it is worth every minute.

Port Isaac is the village the world knows as Portwenn, the fictional setting of Doc Martin, and it would be extraordinary even if Martin Clunes had never set foot in it. A working fishing village of rare completeness and beauty, its lanes genuinely too narrow for modern traffic, its harbour sheltering boats that have worked this stretch of the north coast for centuries. The fame the television series brought has been absorbed with characteristic Cornish good humour and the village is no less itself for it. The Fisherman's Friends — local men who began singing sea shanties on the harbour in 1995, ended up with a record deal, a film, and a West End musical, and still perform here on summer Friday evenings — are the most Port Isaac story imaginable.

Tintagel stands apart from everything else on the Cornish coast, in the way that places built on legend tend to. The castle ruins cling to a clifftop headland on the north coast — half on the mainland, half on a rocky island connected since 2019 by a dramatic new footbridge above a churning Atlantic chasm. Legend says King Arthur was born here, and while the historical basis for that claim is vigorously debated, recent archaeological excavations have found a significant and wealthy Dark Ages settlement — Mediterranean pottery, inscriptions, evidence of a community connected to the wider world in ways that suggest it mattered enormously to whoever built it. The legends, it turns out, grew from something real. The landscape, even without the mythology, would make it worth the journey.

The writers, artists and legends

Cornwall has always attracted people who respond to edges — geographical, emotional, creative. Daphne du Maurier lived at Menabilly on the Gowennap Head near Fowey for 26 years and set Rebecca, Jamaica Inn, and Frenchman's Creek in the Cornish landscapes she knew intimately. Her Cornwall — foggy, secretive, romantic, slightly threatening — is the one that lodged in the cultural imagination and never left. Walking the coast path above Polridmouth Bay, where she imagined Manderley standing, the landscape still feels exactly as she described it.

John Betjeman, the poet laureate, loved Cornwall with a passion he expressed in verse throughout his life. He is buried at St Enodoc Church near Rock, in a churchyard so close to the sea that it floods in winter. Winston Churchill painted at St Ives. Virginia Woolf spent childhood summers at Talland House in St Ives — the inspiration for To the Lighthouse. DH Lawrence lived briefly in Zennor with Frieda, until local suspicion during the First World War forced them to leave. The Cornish have always attracted complicated geniuses and then made life quietly difficult for them.

On our Cornwall & Cotswolds tour from London, we travel through these landscapes — past the engine houses and the harbour towns, through the countryside that du Maurier walked and Betjeman loved, stopping in Port Isaac and exploring the coast that has been pulling creative people to its edges for two centuries. The five days give you time to understand Cornwall rather than merely see it — which is, in our experience, the only way to do it justice.

Getting to Cornwall from London

Cornwall is at the far end of England, and reaching it requires either time or planning — ideally both. The train from London Paddington to Penzance takes around five hours, which is perfectly manageable but puts significant constraints on how much you can see once you arrive. Public transport within Cornwall is limited, and the most interesting places — the Penwith Peninsula, the north coast engine houses, the hidden south coast estuaries — are rarely accessible without a car.

Driving from London takes around four and a half to five hours depending on traffic, which is a long day before you've arrived. The roads improve dramatically once you cross the Tamar, but they also narrow considerably.

The most rewarding way to experience Cornwall from London — particularly if you want to see the best of the county without spending your holiday navigating — is a small-group guided tour that takes care of the logistics entirely. Our Cornwall & Cotswolds tour from London covers five days, combining the Cornish coast and countryside with the Cotswolds villages on the way back — two of the most beautiful landscapes in England in a single journey, with expert guides, hand-picked accommodation, and no planning required on your end.

Cornwall repays the effort of getting there many times over. Every person we've taken there who hadn't been before has said some version of the same thing afterwards: I didn't realise it was like this. I had no idea. Why haven't I come here before?

The answer, usually, is that it seemed far away. It is. And it's completely worth it.

Ready to go?

Browse our Cornwall & Cotswolds tour from London for the full five-day experience, or get in touch with our team to talk through what's right for you. Cornwall is waiting — and it has been waiting, at the edge of the world, for a very long time.