Use the promo code GO26 at checkout

Britain has many beautiful places. It has very few places that stop people in their tracks — that produce, without warning, the specific feeling of being somewhere genuinely extraordinary.

The Lake District is one of them, and it has been producing that feeling in travellers, poets, painters, and writers for over two hundred years without any signs of fatigue.

There is a reason Wordsworth spent most of his adult life here and wrote about it obsessively. A reason Beatrix Potter chose this landscape above all others and refused to leave. A reason that the Lake District became England's first UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2017 — recognised not just for its natural beauty but for the profound influence it has had on art, literature, and the way the world thinks about landscape.

Here is what it contains, and why it deserves your time.

The landscape

The Lake District National Park covers 912 square miles of Cumbria in northwest England, and it contains within that space a concentration of mountain, lake, valley, and moorland that is simply unmatched anywhere else in England. Scafell Pike — the highest point in England at 978 metres — rises from a landscape of seventeen lakes, hundreds of tarns, and fells that turn from green to purple to gold depending on the season and the light.

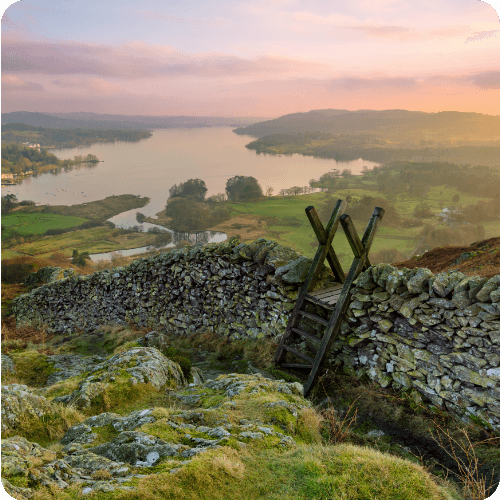

What distinguishes the Lake District from other beautiful English landscapes is its verticality. The Cotswolds rolls. The Yorkshire Dales opens. The Lake District climbs. The fells rise steeply from the lakeshores, giving every valley its own enclosed world — its own weather, its own character, its own distinct mood. Two lakes separated by a single ridge can feel like different countries. The claustrophobic drama of Wastwater, the longest and deepest lake in England with scree slopes plunging straight into the black water, has nothing in common with the gentle, pastoral quality of Windermere ten miles away. This variety, within a relatively compact area, is what makes the Lake District endlessly surprising.

The light does the rest. Lake District light is famous among painters for the same reason Cornish light is — the combination of water, elevation, and Atlantic weather systems produces a quality of illumination that is never quite the same twice and is frequently breathtaking.

Windermere

Windermere is England's largest natural lake — ten and a half miles long, a mile wide at its broadest point — and it sits at the centre of the Lake District both geographically and emotionally. The town of Windermere and the neighbouring village of Bowness-on-Windermere grew up around Victorian tourism, when the railway arrived in 1847 and suddenly brought the landscape within reach of the industrial cities to the south. The Victorians came in their thousands, many of them following in the footsteps of the Romantic poets who had spent the previous half century writing about this place with barely contained ecstasy.

Taking a boat out on Windermere — which our York & Lake District tour includes — is the simplest and most effective way to understand why the lake has held people so completely for so long. From the water, the fells rise on both sides, their reflections doubling the landscape in ways that genuinely challenge the visual system. The Victorian boathouses, the wooded islands, the glimpses of stone farmhouses on the hillsides — it is exactly as beautiful as it looks in the photographs, which is not something you can always say.

Beatrix Potter and Hill Top

Beatrix Potter is one of the most beloved children's authors in history — The Tale of Peter Rabbit, published in 1902, has sold over 45 million copies worldwide and launched a cast of characters that has never gone out of fashion. But the Lake District story of Beatrix Potter is bigger and more interesting than the books.

Potter first came to the Lake District on family holidays as a child, and the landscape — the farms, the dry stone walls, the Herdwick sheep on the fells — lodged itself permanently in her imagination. When Peter Rabbit made her wealthy, she used the money to buy Hill Top farm at Near Sawrey, near Windermere — partly to live, partly to farm seriously, and partly to protect. Over the following decades, working closely with the National Trust and with the Herdwick shepherd and later MP Tom Storey, she bought farm after farm across the southern Lake District, preserving them from development and protecting the traditional farming practices she loved. When she died in 1943, she left over 4,000 acres to the National Trust.

Hill Top, which we visit on our York & Lake District tour, is the small 17th-century farmhouse where she lived and worked during the years she wrote many of her most famous books. The rooms are unchanged — the dresser, the garden, the view from the window, the details she hid in her illustrations — and standing in them is unexpectedly affecting. Potter was not merely a writer. She was a farmer, a naturalist, a conservationist, and one of the principal reasons the southern Lake District looks the way it does today. The National Park owes her more than it can adequately repay.

Wordsworth and Grasmere

Before Beatrix Potter, before the National Park, before the Victorian tourists and the railways, there was William Wordsworth — and without Wordsworth, it is quite possible that none of the rest of it happens.

Wordsworth was born in Cockermouth in 1770, grew up in the Lake District, left for Cambridge and Europe and London, and came back. He and his sister Dorothy moved to Dove Cottage in Grasmere in 1799 and he spent most of the rest of his long life within a few miles of where he was born. His poems — The Prelude, Tintern Abbey, the Immortality Ode — articulated something about landscape and memory and the human relationship with the natural world that nobody had quite put into words before, and they changed how an entire civilisation thought about nature. Before the Romantics, mountains were seen primarily as dangerous obstacles. Wordsworth and his contemporaries turned them into something to stand in front of and feel.

The Lake District became, in effect, the landscape that invented the idea of landscape as something worth protecting for its own sake. Wordsworth himself campaigned against the railway reaching too deep into the Lakes. His arguments — that the landscape belonged in some important sense to everyone, that its character was worth defending from the demands of commerce and progress — were the direct ancestors of the National Park movement, of the right to roam, of conservation as a political value. He was also, incidentally, Poet Laureate for the last seven years of his life and the most famous literary figure in England. His Grasmere cottage is a short step from the churchyard where he is buried, a place of genuine pilgrimage for readers who understand what he did.

Castlerigg Stone Circle

Most visitors to the Lake District come for the scenery and the literary connections. Fewer come knowing they will stand inside one of the oldest and most dramatically positioned prehistoric monuments in Britain. Castlerigg Stone Circle, on a plateau above Keswick in the northern Lakes, predates Stonehenge — constructed around 3200 BC, making it among the earliest stone circles in Europe.

What Stonehenge has in scale and fame, Castlerigg has in setting. The 38 standing stones — the tallest reaching over two metres — are arranged in a circle roughly 30 metres across, with a distinctive rectangular enclosure of additional stones inside. On a clear day, the surrounding fells rise in every direction: Skiddaw to the north, Helvellyn to the south, the entire panorama of the northern Lake District visible from a single spot. The effect is of a monument that was deliberately placed at the centre of a world — which archaeologists believe it essentially was, as a gathering point for Neolithic communities trading stone axes across the region.

We visit Castlerigg on our York & Lake District tour, and the reaction it produces is consistently one of the highlights of the trip. It is proof, if more were needed, that the Lake District's layers run very deep.

Honister Pass

The road that climbs over Honister — connecting Borrowdale in the east to Buttermere in the west — is one of the most dramatic mountain roads in England: steep, narrow, spectacular, and offering at its summit views across the high fells that put the full scale of the national park into perspective.

Honister Slate Mine at the top of the pass has been producing Lakeland green slate since the 1600s, and is the last working slate mine in England. The slate that tiles churches and farmhouses and Victorian terrace houses across the north of England came from places like this — hewn by hand from inside a mountain, at considerable personal risk, by miners who were among the toughest industrial workers in Britain. The mine is still working, the heritage tours go deep into the mountain, and the summit slate products are some of the finest in the country.

The descent into Buttermere — the small lake at the bottom of the pass, surrounded by fells on all sides, with the hamlet of Buttermere village at its shore — is one of those driving experiences the Lake District specialises in: entirely unexpected beauty arriving around a corner that you couldn't see coming.

Sizergh Castle

The approach to the Lake District from the south takes you past Sizergh Castle — a fortified tower house that has stood at this spot since the 14th century and has been home to the Strickland family for over 700 years. It sits at the gateway to the national park, and it represents something important about the landscape beyond it: this is an ancient place, shaped by centuries of continuous human habitation, where the connection between families and land runs extraordinarily deep.

The castle's medieval pele tower — built during the turbulent Border Wars, when Scots raids made stone fortification a practical necessity rather than a status symbol — is one of the finest examples in England. The gardens, managed now by the National Trust, are famous for their rock garden and their extraordinarily coloured autumn foliage. Walking the grounds before heading north into the Lakes proper, you are already in a landscape with an unusually long memory.

The Aysgarth Falls and the Yorkshire Dales

The Lake District doesn't exist in isolation. Arriving from York through the Yorkshire Dales — across the high moorland, through the long green valleys, beside the rivers and waterfalls of one of Britain's most beautiful national parks — is itself an experience worth having, and our tour takes that road deliberately.

Aysgarth Falls, in Wensleydale, is where the River Ure drops through three tiers of broad limestone shelves, creating a series of waterfalls that vary from the thunderous to the theatrical depending on the season and the rainfall. Turner painted here. The falls featured in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves — the scene where Kevin Costner's Robin fights Little John on a narrow bridge, which gives you some sense of the scale. In full flow after winter rain, Aysgarth is magnificent.

Askrigg, nearby, is the village that All Creatures Great and Small — both the original James Herriot series and the recent BBC remake — used as its fictional Darrowby. Herriot's books, set in the 1930s and 1940s and describing the life of a country vet in the Yorkshire Dales with warmth and precision, captured something about this landscape and its people that resonated worldwide. The books have sold over 60 million copies. The village looks, largely, exactly as the series depicts it: stone-built, unhurried, and set in a valley of exceptional beauty.

Why visit the Lake District

The Lake District is one of those places that resists being rushed. A day here produces beautiful photographs and a strong desire to return. Two days begins to give you a sense of the place. Three days — as our York & Lake District tour from London provides — starts to give you something closer to understanding: the way the landscape changes between morning and afternoon, the way different valleys have entirely different characters, the way the fells look from the water, the way the light falls on Windermere at dusk.

It also gives you time to follow the literary threads — from Wordsworth to Potter to Herriot — that connect this landscape to a long history of writers who felt the same pull you will feel and tried, with varying degrees of success, to describe it. The pull itself is easier to understand once you're standing in it. The difficulty of describing it is apparent immediately.

England's most celebrated landscape earned that description honestly, over a very long period of time, one extraordinary view at a time. Our Lake District tour from London and York gives you the access, the context, and the company to make the most of it.

You're going to find it hard to leave.